PIIKANI BLACKFOOT TEACHING

ELDERS: DR. REG CROWSHOE

AND GEOFF CROW EAGLE

INTRODUCTION (audio narration)

topThe Piikani Nation is part of the Blackfoot Confederacy. The Siksika, the Bloods, and the Piikani all speak the Blackfoot language, and we’re all part of Treaty 7 in southern Alberta - along with the Tsuu T’ina, or Sarcee, who speak a different language.

When they put in the border for the United States, they put it right through our Piikani territory. Half of us were sent to the states and the other half went north. So we became the northern Piikani. The Southern Piikani are across the border in Montana.

At the Old Man River Cultural Centre on the northern Piikani Nation, we’re working to preserve, protect and renew our Piikani culture. As we listen to our stories, speak our language, sing our songs, and participate in our traditional societies, we gain insight and extract the understanding we need to live well and keep our ways alive. A lot of our young people today may not understand what our elders say, because we have to translate our culture back to many children through the western school system. So we all have to work together in order for our children to be brought up in a good way: to find their identity, to get guidance on what to do in life, to be instruments of the Creator, and to carry on our culture. Because our culture should always be steering us, leading our way of life.

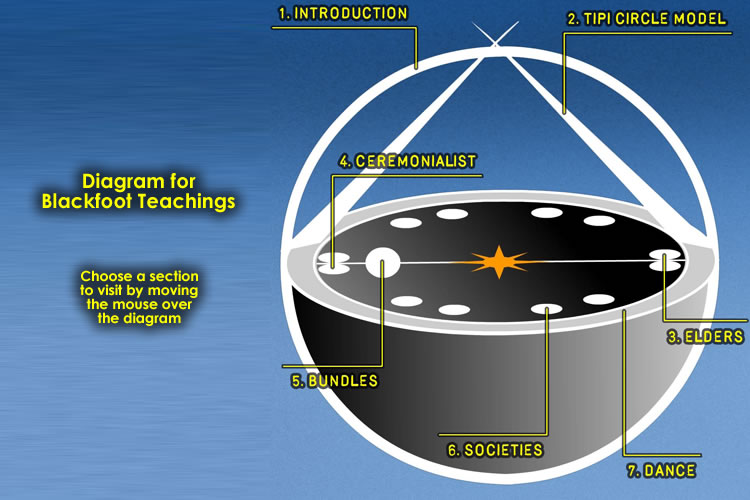

So it is with great reverence for our cultural knowledge that we share with you the Blackfoot Tipi model and a little bit about our Piikani processes, which we have identified through our work at the centre. We want these systems to form the basis of Piikani governance, education and other forms of community life.

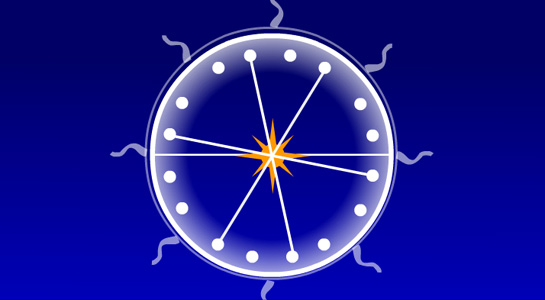

Many elders believe that there is an oral circle, or system, that exists across all the first nations of North America, and that we are all a part of. Our Piikani Blackfoot systems are only a part of that greater circle. We are honoured to share with you our Piikani perspective, as part of that great circle that unites us all.

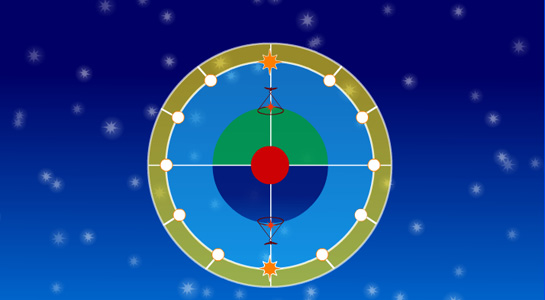

TIPI CIRCLE MODEL (audio narration)

Our homes are sacred in our traditional way of life. Our Piikani Blackfoot system came from our tipis, where we sat in a circle. If we’d had a square structure, then maybe we would have had that kind of system, but in our case it was a circle.

We’re looking at a bird’s eye view of a tipi. If you were a bird sitting on the poles and looking down into the tipi, this is what you’d see in a Blackfoot tipi setting:

First of all, our traditional circle structure had a female side and a male side.

In the centre is a fire. And people sit around the outside and people sit in the middle, closer to the fire. Opposite the door to the west is a place of honour, where we put our sacred bundles, which represent our sources of authority and legislation for the community. To the north of the fire would be a place where we might look after a sacred pipe.

And then just in front of our bundles we had a place where we had the smudge altar. To the north of that altar was where the tobacco cutter sat. Closest to the door is where the helpers sat. And south of the fire is where we put the drummers.

And then sitting around the circle on the female side, we have the female ceremonialist, and then the host. Other bundle owners that represent the same kind of discourse sat on the female bundle owner’s side. And then former bundle owners and other ceremonial grandmothers sat next to the door. And it was the same on the male side: the host, other male bundle owners, and then male bundle grandparents, or elders, sitting next to the door.

That was pretty common across all the ceremonies, how you would see people sitting in a circle. And at one time all the people in that circle had a place in relation to the Blackfoot societies. The societies had the administrative roles: looking after policing and social services and education, and so on – all our Piikani processes.

A traditional Piikani Blackfoot process has four parts: venue, action, language and song. So if I say I belong to the Thunder Pipe society, for example, I need to be able identify myself to the Thunder Pipe community in those four ways: I need to be able to sit in their venues, to demonstrate my ability and qualifications through certain actions. I need to speak their language and sing those Thunder Pipe songs that give that authority. If I can’t do all these with respect and understanding, then I can’t be a part of their society or discourse. This is how we would protect or give authority to information, or to a concept.

So in that circle structure, there had to be respect, and that’s what we’re missing today; we don’t give respect to information. We’re so busy rushing through our tasks that we don’t take time to make sure that understanding happens with respect.

With the circle model, we conduct business with respect and integrity, as well as focusing on the task at hand - so that understanding and learning is a lot deeper than it is if we just take it as a task.

ELDERS (audio narration)

In Piikani society, an elder is somebody who has looked after a bundle that helped the community, and who has passed on that bundle and become a ceremonial grandparent. The ceremonial grandparent can be called back to conduct or oversee ceremonies. And you look to them for guidance, and consult with them.

We asked our elders about how to communicate between a white man’s world and an Indian’s world - because the world we live in today has so much confusion, and this causes a lack of communication, which leads to conflict.

We wanted to look at how we view the world from our Piikani belief systems - those forms of knowledge that have been in place for thousands of years.

So we asked our Elders: who are we as Indian thinkers? Our Creation stories; what do they say? And a lot of our stories said that humans were created as equal to all creation. And the concept of being equal defined our thinking and understanding. So I was equal to the animals and plants, the air and the water; the stars were equal to me, and I was equal to all human beings, and even to bugs.

Now the concept of being created equally was the basis of all our practices - our forms of governance, and social relations. We are all created together, and all are sacred. So our Piikani Blackfoot language and oral system are based in ceremonial practices; a ceremonial circle structure was our way of communicating and working in a group.

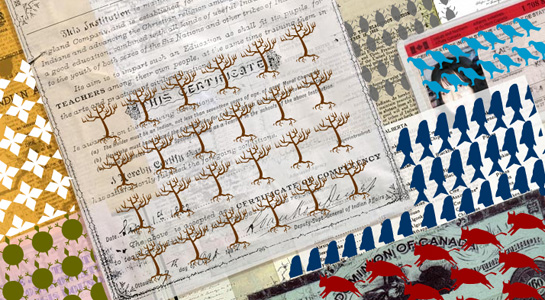

Then we asked our elders: What is a white man thinker? And they recalled the saying, “God gives dominion to man.” We were taught in residential school that this dominion gives man the right to be superior over all Creation: over the plants, animals, rocks, even the skies. This type of thinking was new to our elders; because if you’re superior to everything, then the power to make decisions and build credibility is given to man; it’s not in Creator’s hands any more.

The word “dominion” used to appear on all the government documents. Every document the Indian agent gave out had “Dominion of Canada” written on it. So we had to learn a new language based on the idea of the superiority of man. And authority was now held in written documents, rather than rites transferred through song and ceremony. And we look to documents for authority today; we ask, “What kind of paper does he have?” This defines leadership now: the products owned and acquired through dominion, authorized by the written word, and controlled by a hierarchy that places man at the top of all creation.

All these concepts were embedded in the white man’s education, government and religion. And today we have to operate within that perspective. This creates challenges for us, in passing on traditional Piikani knowledge to our children.

If we’re going to keep our culture alive, we need to involve our elders and ceremonial grandparents in our operations. So we took the circle model that our Elders had, and started working with that - looking at how to interpret that so we can use it today.

For example, when we discuss things or make decisions, the topic is like a sacred bundle – it should be opened respectfully and understood with care, as deeply as possible. We still have a smudge altar, which is parallel to the gavel used in modern boardrooms to start meetings. And we still need our elders at the door, to advise and watch over us, and help us to respectfully manage our process. These are just a few examples of how we have been adapting our circle model, and the knowledge of our elders, to the modern world.

CEREMONIALIST (audio narration)

This circle structure and all our oral systems are based on ceremony and rituals, or rites. Two basic rites are gifted rites and transferred rites. A gifted rite is an authority that was gifted to you; maybe the spirits gifted you on a vision quest with a rite, or a certain amount of knowledge that needed to be protected. A transferred rite came from the time of Creation and is tied from that original time right down to how we maintain that rite today. All of these rites are responsibilities we carry that make us part of the community.

People with transferred rites are caring for knowledge that is from a sacred source. It is not a guessing game, or something they made up. And they work hard to earn the privilege of that knowledge. If you get a transferred rite, you have to practice that rite every day, walk that way for the rest of your life.

When you get a transferred rite, it’s a rebirth in life; it doesn’t matter how old you are. Once you have made that vow you have humbled yourself to the Creator. It is understood then that you will need a basic understanding of how to live with kindness and humbleness put together; you have to strive to be a genuine person, to not be phony about things.

When we got into the Brave Dog society, all the members were sitting in a circle in the Brave Dog Tipi at the Sun Dance, which is the when the Brave Dog Society members come together. When it was our turn to have the bundle transferred to us, we got up and went to the north side, where the main leader of the Brave Dogs was sitting. And we stood there with the owners, four of us: two men and two women. And the singing and drumming started, and we danced four times on each of the four corners of the fire pit. On the fourth time, we were given that bundle, and instructions in our language on how to take care of it. And the Piikani people that were taking part in the Sun Dance sat outside witnessing what was in the tipi. So nobody can argue that it was not a legitimate transferred rite.

So if I do a transfer to someone else, I have to understand and practice all those ways that were shown to me, through those four aspects of our Piikani legal process: the venue, which was the Brave Dog Tipi at the Sun Dance; the actions of that specific dance; the language, which was the instructions on caring for the bundle; and the song that went with that transfer.

All this ceremony lends meaning to our processes. That’s why we still have the memory of our Treaties today. When Crow Foot signed Treaty Seven, our Blackfoot witnesses said he came out of his tipi singing songs. And before he even went out to sign the treaty, he came out of his tipi, and he said, “All of you in this place where we camp, you are my children. I’m going across the river to sign some papers. And those white people over there will be my children too.” And before they went across, all the chiefs had a ceremony, and they prayed, and danced. Only then did they go across to sign the treaty. So that treaty’s not just paper: it has an emotional side, a spirit. As the grandchildren of those chiefs who danced and prayed, it’s in our blood.

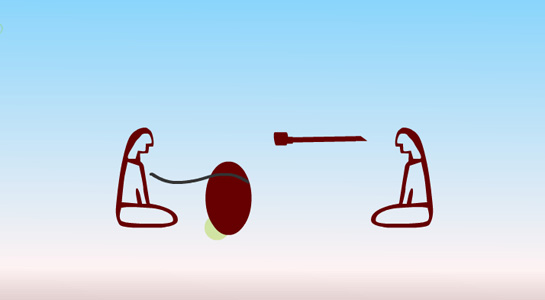

BUNDLES (audio narration)

Our traditional elders taught us how to make decisions. And a lot of our decision-making comes from bundles. A holy bundle is never owned by one person or family, but it can be transferred to someone that wants to be a custodian, to take care of it. And a person can be refused.

Each bundle holds different relics, and all have meaning. A lot of bundles have birds and animals, such as an owl or eagle. And those are rolled together and put in the bundle. And when those birds and animals put themselves in that bundle as a spiritual gift from the Creator, they’ll even give a song; each article that’s in the bundle has its own venue, action, language and song.

Once or twice a year, that bundle will be opened, and somebody will make a vow to that bundle, to a certain holy object that’s contained within; for example, they may vow to the Creator to dance with a certain relic in that bundle, so that someone who is very sick will be healed. And payments are made, as you make that vow to the custodian.

There are many bundles. The Brave Dogs usually have a rattle, sacred paint, feathers, and some other holy objects that we can’t talk about. And usually a bundle carrier will have a pipe. When the Brave Dog Bear Bundle was going to be transferred to us, we offered a pipe to the custodian. So when we joined the Brave Dogs, I had to get another pipe to help me in that journey with the bundle. In turn, when I was going to give that bundle away, the new member approached me with a pipe. Some pipes are in with the bundle, some you have separately to practice with ceremonies.

We had our own legal system. For example, not anyone can open a bundle; only the person with transferred rights will be the one that’s going to do that. They need to know the songs, the proper action, the language, and it all has to take place in the right venue.

Our legal system came from the Creator, as a gift to help us make decisions. So when you make a decision, you smudge, and pray, and ask the Creator to be part of your decision-making. We never jump the protocol. The Creator’s always there in our decision-making, so it’s always legitimate, even if it’s a very technical decision you have to make.

SOCIETIES (audio narration)

The Creator gifted all his creations with systems of governance. Our Blackfoot Societies were such a gift – they were our education systems, our administration, our military and police. In the Blackfoot nation there were many societies 100 years back, such as the Bumblebees, the Fly Society, the Worm Society, and so forth.

Societies were graded by age. Children went into a society at a young age, where they stayed a few years before moving to another. For example, the Chickadee society, they’re 8 to 12 years old, and from there they might go to the Prairie Chicken Society, and they would be elders to the Chickadees. It was a learning process, teaching children how to discipline themselves in their mind, body and spirit. And when a child grows up he goes into the appropriate adult society.

For a time it was illegal to practice our traditions in Canada. The societies aren’t underground anymore, but some of the societies that existed 100 years ago are no longer practiced. Some older people still have these rituals. But if we don’t go and ask them about it, we’re going to lose them.

In Piikani country, there’s two known societies today: the Brave Dog society, and the Neepomakeeks, the Chickadees. And the Blood, Siksika, Sarcee and South Pikaani still practice the Horn societies, the Magpie society, the Dove Society and the Brave Dog society.

If you are in a society and really practice their ways, you have the right to sing their songs at any time: if you’re going to meditate, or say a prayer, even if you’re going to do a presentation. If you feel that you need spiritual help, you could sing to help you speak well, have that power given within you to reach out to the people. And that’s where that power is. If you are talking to somebody, and that person really gets it, and feels good about that information, you’ve transferred the power of understanding to that person. It’s real. This is a power that we often overlook. Sometimes we think of powers as making a lot of strange magic. But we neglect who we are, the magic within us. Our traditional Piikani societies help identify and mold who you are, to see yourself as a total being, having all these gifts from the Creator. If you don’t look at yourself that way, if you neglect yourself, you miss the whole point. You have to look at yourself as a whole person: mentally, physically, spiritually, emotionally. All those have to be intact, along with your five senses.

A lot of people don’t really understand our five senses. They talk about discernment. But most of the time today, we don’t really pay attention. True discernment means really feeling something as a gift from the Creator. I only understood that when I went on a vision quest. When I was fasting on that hillside, thinking, praying, singing so hard in my Blackfoot tongue, my senses went beyond a normal state of mind. I could hear things I can’t hear in public, things I never heard before. And my sight was really right on target. And everything smelled so precious, so good. Even my taste: I could taste good things, taste the smudge. And the feeling – my hands and my body, everything – they were all connected. And where I sat, I found it so sacred, so beautiful. I knew it didn’t belong to me; I was just sitting on Mother Earth. That was my protection from anything. And when I started studying what was told to me at that time, I understood what discernment was. Discernment means seeing with your naked eyes, bringing back the message to your feelings, and smell, and taste, so you feel that message with the full attention of your whole being. And if you hear something, like drumming, or a song, that message, what it really is, will be brought back to your feelings – but you expand it more. That’s discernment.

And our societies, our education systems, were designed to bring us to this place of discernment, and respect for everything around us.

DANCE (audio narration)

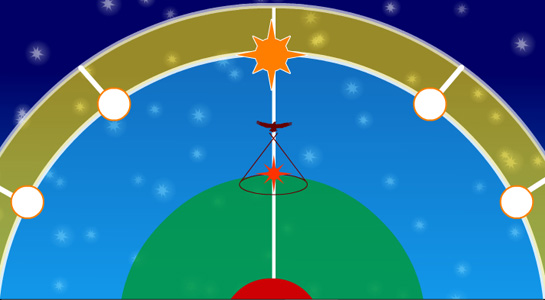

When we talk about our Piikani Blackfoot concepts of authority and governance, first of all we talk about our Sun Dances that brought the communities together.

We won’t talk about Sundance here because that is very sacred. But we can talk about Powwows. The powwow is a gathering of all the people, where nations come together, with drummers and dancers.

To some people, the powwow has a really superficial meaning: beads and feathers, and the song, and the drum, and so on. And they’ll say, well, that looks beautiful. But Indian thinkers will look at traditional status. That man that’s out there dancing: if he’s got a headdress on, he has a song to allow him to wear that headdress; if he’s carrying a rattle, he has a song that allows him to carry that rattle. It’s attached to our belief system. So we have different types of people sitting in the crowd looking at the powwow, or being part of the powwow.

If you don’t really know how to identify a dancer at the powwow, or at a Sun Dance, well you’ve missed the whole answer to the person dancing. But it you really look at that dancer, you’ll be able to see: he’s mimicking something in his own identity. His actions are a language used in that powwow circuit. And for some their dance is talking, in its own way, with whoever they are communicating with.

For example, in Blackfoot, apshkaukshin means you’re making that motion, that action, because you want to dance away illnesses, bad luck, all the problems, hurts, injuries or emotional scars that were put on you, or maybe something bad that happened just recently. Or if somebody’s saying bad things about you, you can do apshkaukshin too. And when you’re dancing, mimicking your dream or how your ancestor used to dance, you’re making those motions to get those things away from you. It’s like you have a shield, and somebody’s shooting at you; you’re going to duck away from that.

And our elders tell us: when you sit and meditate, when you pray, apishkokisit. It’s like you have your medicine shield, and you’re making motions to all bad things to go away from you. And that’s so important, that action. It gives you strength, a sense of identity and purpose, a greater understanding of what you’re doing.

This elder told me once, “When you pray, little brother, apstimaukshokshit.” He says, “don’t be ashamed of prayers, of the Creator. Even if you’re all by yourself, you may look silly, but the thing is, you make that motion. So apshkaukshin is a really good example of how our great circle system, our great dance, is always a ceremony, a language, a way of speaking with the universe - no matter which way we turn, or what we have to go through.